3D bin packing using a genetic algorithm

TLDR

- I implemented a solution for three-dimensional packing with support for orthogonal rotations of objects and different container types.

- The solution combines a genetic algorithm (searching the solution space) with a packing heuristic based on Empty Maximal Spaces (EMS).

- The chromosome encodes: packing order (BPS), orientations (VBO), and container selection order (CLS).

- The best space-selection heuristic was DFTRC-2, and the most suitable crossover operator was one-point crossover (SBX/uniform were not suitable).

- I compared packing heuristics and mutation rates.

Motivation

Packing problems appear in the literature as early as the 1970s, first in 1D and 2D forms. Early approaches were simple heuristics like First-Fit and Best-Fit, while with increasing computing power the focus shifted more toward metaheuristic solutions (especially from the 1990s to today). Practical applications are common: logistics, warehousing, transport planning, manufacturing, and generally any system where we want to minimize the number of containers or maximize volume utilization.

This problem is NP-hard, so in practice approximation and heuristic approaches are often used.

What I find especially interesting is that the problem has been present in industry for a long time, yet it is still actively researched due to its complexity and practical importance.

This work focuses on the 3D variant with realistic details such as rotations and non-homogeneous containers.

Problem

We have a finite set of objects, where each object i is defined by dimensions (wᵢ, hᵢ, dᵢ). Each container b has dimensions (Wᵦ, Hᵦ, Dᵦ). The goal is to assign each object to a container and a position (and potentially a rotation) such that:

- objects do not overlap,

- each object fits into its assigned container,

- and we use as few containers as possible (equivalently: minimize unused volume).

Objects can be orthogonally rotated, which is equivalent to permuting dimensions, so each object has up to 6 configurations.

Approach

The solution consists of two components:

- A genetic algorithm (GA) that searches the space of solutions (orders and orientations).

- A packing heuristic that, for a given chromosome, tries to construct a concrete layout in containers and returns how many containers are required.

In each GA iteration:

- individuals are evaluated using the packing heuristic,

- selection is performed,

- crossover and mutation are applied,

- and the process continues across generations.

Solution encoding (chromosome)

An individual’s chromosome is a vector of length 2n + m:

- the first n real values in [0,1] encode BPS (box packing sequence),

- the next n values encode VBO (orientations/rotations),

- the last m values encode CLS (container loading sequence), relevant if containers are not homogeneous.

Why real numbers in [0,1]?

- they allow simple mutations and crossovers,

- and the order is obtained by sorting objects by their assigned value.

Rotations are not encoded directly as {0..5}, but as a coefficient that is later mapped to one of the allowed rotations in the current container context.

Packing heuristic

Empty Maximal Spaces (EMS)

Free space in a container is represented by a list of EMS volumes: each EMS represents the largest rectangular empty block currently available in the container. After placing an object, the EMS list is updated:

- select an EMS that can fit the object,

- generate new EMS blocks based on the intersection of the object and the selected EMS,

- remove degenerate or redundant EMS blocks,

- optionally remove EMS blocks that cannot fit any remaining object.

In practice, the object is positioned in the back-bottom-left corner of the selected EMS, which limits the growth in the number of newly created EMS blocks and keeps the space compact.

EMS selection heuristics

I implemented and compared several heuristics:

- First-Fit: take the first EMS that fits the object.

- Best-Fit: take the smallest EMS that fits the object.

- DFTRC-2: choose an EMS so that the object (in some rotation) ends up farthest from the front-top-right corner of the container (Front-Top-Right).

DFTRC-2 is effectively a local search: for each object it checks all allowed rotations across all EMS blocks and selects the best option according to the distance criterion. In the actual packing step, the rotation stored in the chromosome is still used, so the chromosome continues to have a significant impact on the final outcome.

Genetic algorithm

Selection

I used elitism (e.g., 5% of the population stays untouched) and tournament selection:

- randomly pick 3 individuals,

- choose the best,

- repeat for the second parent.

Crossover

Crossover turned out to be unexpectedly sensitive because of the encoding:

- the same gene in different chromosomes can imply a completely different order after sorting,

- so mixing genes without context often destroys structure.

Because of that, SBX and uniform approaches did not perform well (weak learning rate; the best individual was often obtained almost randomly). The best approach was one-point crossover:

- choose a cut point,

- offspring take the left part from one parent and the right part from the other,

- offspring preserve structural blocks and end up more similar to the parents.

Mutation

Mutation iterates through each gene and, with a small probability, replaces its value with a new one from [0,1]. I tested multiple mutation rates (1%, 5%, 10%) to find a balance between stability and exploration.

Fitness function

The simplest fitness would be:

- the number of used containers.

However, if two solutions use the same number of containers, it helps to further distinguish packing quality. Therefore, the fitness also includes the relative fill of the least utilized container, e.g.:

Fitness = number of containers + (least utilized volume / container capacity)

This provides a finer grading between solutions that use the same number of containers. The problem is a minimization problem: the goal is to reduce fitness.

Results analysis

Stopping criterion

On simpler instances, the optimal solution appeared after only a few dozen generations, while on more complex instances there is fast early learning followed by stagnation after ~100 generations. As a practical stopping criterion I used 100 generations, and repeated each measurement 20 times.

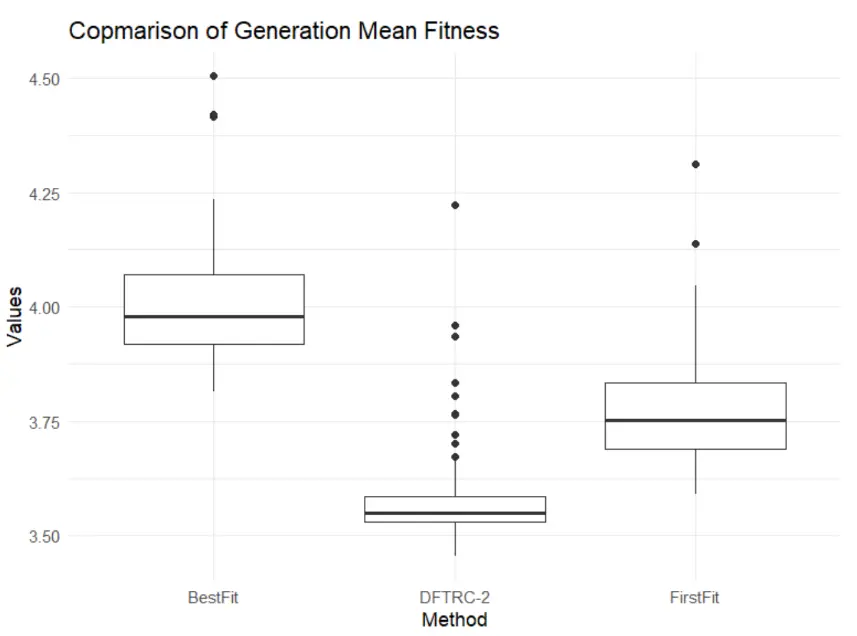

Comparison of packing heuristics

The packing heuristic has a major impact because evaluation constructs the full solution. In tests, DFTRC-2 clearly outperformed First-Fit and Best-Fit.

Interestingly, First-Fit performed better than Best-Fit, even though intuitively Best-Fit should often fill space better. In practice this depends on EMS dynamics and how choosing a smaller EMS affects future packing options.

Comparison of mutation rates

I tested 1%, 5%, and 10% mutation:

- 1% can be great if it finds a good individual early, but it often gets stuck and overall was the worst option.

- 10% provides more exploration, but it can break good structures.

- 5% was the most stable compromise and on average produced the best results.

Conclusion

Three-dimensional packing, while it may look trivial at first, is a very interesting and challenging optimization problem that has been relevant for decades. In this work I implemented a solution that combines:

- GA (search in the solution space),

- EMS (free-space representation),

- and DFTRC-2 (space selection heuristic).

The analysis showed that:

- crossover operators like uniform and SBX are not suitable for this kind of encoding,

- one-point crossover preserves context and yields a better learning rate,

- DFTRC-2 dominates simpler heuristics,

- and 5% mutation is a good default for stable progress on more complex instances.

Further ideas

- Add additional constraints (maximum weight, rotation restrictions, fragility).

- Try alternative chromosome representations (e.g., direct permutations with specialized crossover).

- Compare GA with other metaheuristics (simulated annealing / tabu search) on the same instances.

- Parallelize population evaluation (evaluation is often the most expensive part).